PREVIEW

FIRST PERSON DISPATCHES | Arguments and debates about the issues that matter most to Africa | By Tim Concannon

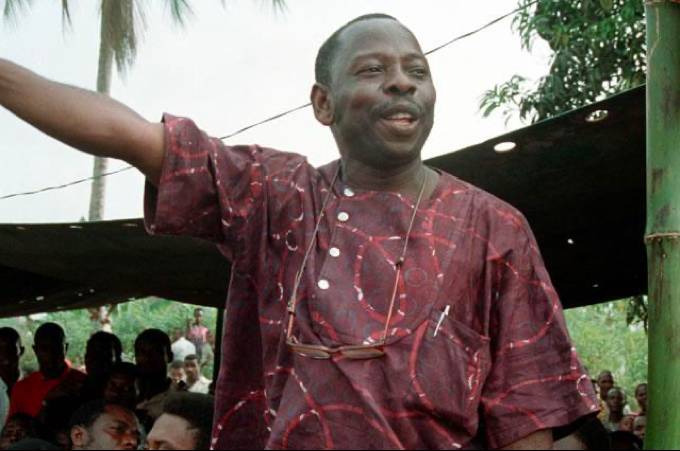

Ken Saro-Wiwa, Ogoni rights leader, executed by the Abacha regime in 1995 for opposing Shell's pollution. The anniversary of his killing falls on 10th November, 2 days before the end of the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow. Photograph: Tim Lambon/Greenpeace

Protests in Britain by Extinction Rebellion this year have seen two constant features: confrontations with police, and First Nation activists from Central and South America calling for an end to the oil business.

After a pandemic lull, the environmental group which Britain's Home Secretary Priti Patel has labelled an extremist organisation has become increasingly militant.

Its agitation is expected to intensify leading up to the COP26 intergovernmental climate summit in Glasgow, opening on 1 November.

It may surprise many of the (mostly white) activists in the movement to discover that leading members of at least one indigenous 'tribe', once held up as a vanguard of opposition to the global oil industry – the Ogoni minority in Nigeria's oil-producing Niger Delta – are inviting oil companies back onto their land, subject to certain conditions.

Amazonian activists join Extinction Rebellion in protesting BlackRock's oil investment in the Amazon basin, London 2019. Photograph: Extinction Rebellion

Yes, you read that correctly.

The non-violent Nigerian protestors… whose campaign to kick Shell off their land worked in 1993… but then triggered a military crackdown and occupation, which caused the deaths of thousands of Ogoni including the writer Ken Saro-Wiwa, and Nigeria's suspension from the Commonwealth, now want the oil industry back.

Back in the 1990s, the Ogoni dominated the news and were lionised by Anita Roddick, William Boyd, Harold Pinter and Salman Rushdie.

The Ogoni's about turn on oil exploration comes just as the European Union, Britain and other former colonisers of Africa, the Asia Pacific and the Americas insist they're getting out of oil and gas.

Royal Dutch Shell, the Big Bad of 1990s anti-oil activism, is quietly meeting one of the protestors' demands from 20 years ago. The oil company is planning to withdraw from onshore oil production in Nigeria to concentrate on large offshore fields.

Shell also insists it's getting out of oil altogether eventually. But a third of its shareholders were won over by activists' arguments this year that Shell is dragging its feet over the mounting climate emergency.

The oil giant calls a Dutch court order to cut 45% of its carbon emissions by 2030 'unreasonable'; it insists this exceeds the promises made of the EU and industry rivals. Instead, Shell offers to make a 20% cut.

Activists are set to turn up the heat on Shell at COP26 as it backs private-equity firm Siccar Point's plan to explore for new oil reserves in the Cambo oilfield off Shetland in Scotland.

This could cause friction in the coalition of the Scottish National Party and the Green Party that is governing Scotland, which hosts COP26.

The minority Greens oppose new oil extraction. Since she was re-elected in May, Scotland's First Minister Nicola Sturgeon has shifted towards her Green coalition partners on oil. She has called on British Prime Minister Boris Johnson to 'review' the Cambo licence.

Scotland's government may be frozen out of COP26 by Johnson's ministers in London who have led the international lobbying ahead of the summit. Johnson fears that Sturgeon and allies may exploit the limelight they will get at the summit to help a likely legislative push in the parliament Edinburgh for a second Independence referendum.

There will be a focus at COP26 on the splits and divisions between the rich countries who are net oil consumers, who have also been global colonisers.

The really important split is the one between the former coloniser/oil-consuming countries and the oil-producing countries, many of which were made poor by European rule long before their oil and gas assets were discovered.

Iraq's deputy Prime Minister Ali Allawi has called on fellow oil-producers to shift to renewable energy to meet a global zero carbon goal in 2050.

Ali Allawi is very much in a minority among OPEC governments and major oil-exporters. After its price war with Russia at the start of the pandemic Saudi Arabia's monarchy takes the opposite view. Energy Minister Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman is reported to have told a Bank of America meeting in June: 'We are still going to be the last man standing, and every molecule of hydrocarbon will come out.'

The reasons behind the call from Ogoni activists for oil production to resume on their land are complicated. Some are driven by incentives to make money from rents and contracts.

Factions have grown up in Saro-Wiwa's campaign, the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP): rival leadership contenders claim to have a veto on oil's return to Ogoniland. (In the interests of full disclosure, I should add that MOSOP was my employer in the late 1990s).

The optics of this, a quarter century after Saro-Wiwa's execution made headlines, are confusing. In the global environmental movement bringing oil companies back to Ogoniland will seem like a betrayal of a noble cause.

It's easy to dismiss this as corruption. Five years ago, a former British Prime Minister, David Cameron, was caught calling Nigeria 'fantastically corrupt' over tea with the Queen and Archbishop of Canterbury. This year, determined reporting has raised big questions about the ethics of Cameron's use of political contacts in lobbying on behalf of Greensill Capital for state contracts before the company collapsed.

Corruption exists in civil society in Africa as it does in the British government or the Church of England. But the factional leaders of MOSOP are also responding to the demand of over 800, 000 Ogoni for jobs and livelihoods. The oil industry which they kicked out in 1993 now seems like their best bet. This is despite the abundant evidence of pollution and environmental destruction in the region.

Oil's toxic legacy in the Delta

In 1995, when Saro-Wiwa and his eight co-defendants were languishing in prison before a military tribunal handed down the death sentence on the orders of military leader General Sani Abacha, western leaders were preparing a response.

Britain's Prime Minister John Major and United States President Bill Clinton considered a naval blockade on Nigeria. This was revealed in documents released in 2019.

Twenty-five years later, the worst pollution on Earth – according to a 2011 United Nations environmental report on the oil industry's impacts on Ogoni – now goes mostly unreported outside Nigeria, as does the desire of many Ogoni activists for oil jobs to return.

They will not be working for Shell. The one thing on which Ogoni activists and Shell agree is that Shell isn't going back to Ogoniland.

Nigeria's President Muhammadu Buhari has awarded the licence to mine oil from Ogoni (OML 11) to the state-owned Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation, NNPC.

That decision was upheld last month by an Appeal Court judgement, after Shell had challenged the award.

Under the new Petroleum Industry Act, the NNPC can undertake commercial joint ventures. But many in Nigeria doubt the oil wells in Ogoni will begin pumping again soon.

Several reports by independent journalists have covered the slow progress of the clean-up in Ogoniland. Other journalists took money to write more favourable stories on the drawn-out clean-up.

Yet it's striking that decades of oil spills in Africa, on a scale which dwarfs BP's 2010 Deepwater Horizon spill in the Gulf of Mexico, barely warrants attention by news organisations, mostly domiciled in former coloniser countries and mostly run by old white men.

Why ever, in an era when august institutions insist Black Lives Matter, could that be?

The devastating pollution in Ogoni was caused in the 1980s by Shell's creaking oil pipelines and then by 'artisanal refining' and 'bunkering', often euphemisms for oil and gas theft from an already-leaking network.

Local refiners use dangerous homemade stills, often wading knee-deep in raw petroleum, exploiting the creaking infrastructure to steal the oil. Saboteurs also set fire to it for compensation.

Ogoni farmland should be the most fertile in Africa. At the end of the Niger River, it's saturated in nitrates. But compensation claims have turned the economics on their head. Despoliated land is worth more to farmers when it's poisonous to humans and other animals than it is being used to grow crops.

The blame game is endless. On the local level, many oil company officials and locals collude with the state in its various forms to profit from spills and fires.

In 2019, Transparency International and CISLAC published a report claiming the Nigerian army's involvement in a global criminal operation to steal oil on an industrial scale, as much as a fifth of the country's production.

Nigeria's Vice-President Yemi Osinbajo has promoted modular refineries as a way to bring the 'artisanal' refining industry inside a more regulated and legal and theoretically safer framework.

In 2003, I travelled to see what was at the time a recent spill at Yorla in eastern Ogoni (I'd been sent by Friends of the Earth in the Netherlands to scout for a court case).

Locals showed me wellheads which had, mysteriously, not been capped with concrete to prevent theft or accidents on Shell's exit from the region in 1993. Shiny new face plates had been fitted to officially inoperative oil wells not long before, by Texan firm Boots & Coots, after a previous spill.

I looked over to the adjoining creek. A young lad was crouched in muddy, oily water collecting water in a red plastic bowl. Above him was a solar array on a high tower, which I took to be a water pump powered by the sun. Why, I asked, was the little boy having to crouch in a muddy pool to collect water for his family when there was a new solar pump?

Shell had been to install the pump for a photo opportunity, I was told. It had never hooked the expensive device up to the water table because it would have cost more money to provide the people of Yorla with clean water.

The dynamics of local oil production and its links to pollution are complicated by the simmering conflict in the Niger Delta. Although the official ceasefire has mostly held since 2009, oil rebels could still resume armed struggle and join up with other insurgencies that are now threatening to break up Nigeria's federation; into smaller autonomous units if not full secession.

Like their Niger Deltan compatriots, some Ogoni nationalists dream of their 404 square mile region as one of several oil emirates, perhaps part of a new Biafran state.

Yet firebrand secessionists tend to fall out with one another. This may reassure President Buhari and those Ogoni activists, who (contrary to popular belief) don't want to leave the Federation. There's a long memory of Biafran tanks rolling into Ogoni oil-fields within days of the declaration of the breakaway state in 1967 and the terrible violence which followed.

With the the pandemic eviscerating jobs in the Delta across the board, there are few prospects, outside the hydrocarbon economy, that offer the Ogoni the prospects of economic growth.

The Presidential Amnesty Scheme for 'retired' militants is mired in allegations of corruption, as is the Niger Delta Ministry and the Niger Delta Development Commission which is charged with training the region's youth and advancing the Delta economically.

The Petroleum Industry Bill whittled down the amount allocated from state coffers to be re-allocated to 'producer communities' from the 10% demanded by the Southern Governor's Forum, to 3%.

So, this leaves a few choices for Ogoniland. Either citizens, officials and companies can organise the return of onshore of oil and gas production as long as regional and global demand holds up, perhaps for another quarter century.

Or citizens can bet on an entirely new economy opened up by internationally-backed $1 billion clean-up of the region despoliated by its first wave of oil production.

Two years ago, high-level officials close to the process briefed Africa Confidential that the clean-up is beset with inefficiency and financial mismanagement.

Yet if the environmental campaign worked as it was originally conceived, as the largest clean-up operation of its kind on Earth with accountable financial management– it could employ locals for the vast majority of work and create an employment bonanza.

And then it could lay the groundwork for a transition to a greener economy in the Delta, the return of farming and fisheries, and sundry artisanal enterprises, this time perhaps with green hydrogen and solar supplying the energy.

Copyright © Africa Confidential 2024

https://www.africa-confidential.com

Prepared for Free Article on 27/07/2024 at 02:44. Authorized users may download, save, and print articles for their own use, but may not further disseminate these articles in their electronic form without express written permission from Africa Confidential / Asempa Limited. Contact subscriptions@africa-confidential.com.