PREVIEW

The challenge this year is to convert a decade of faster growth into jobs and higher living standards as political tensions rise in the biggest economies

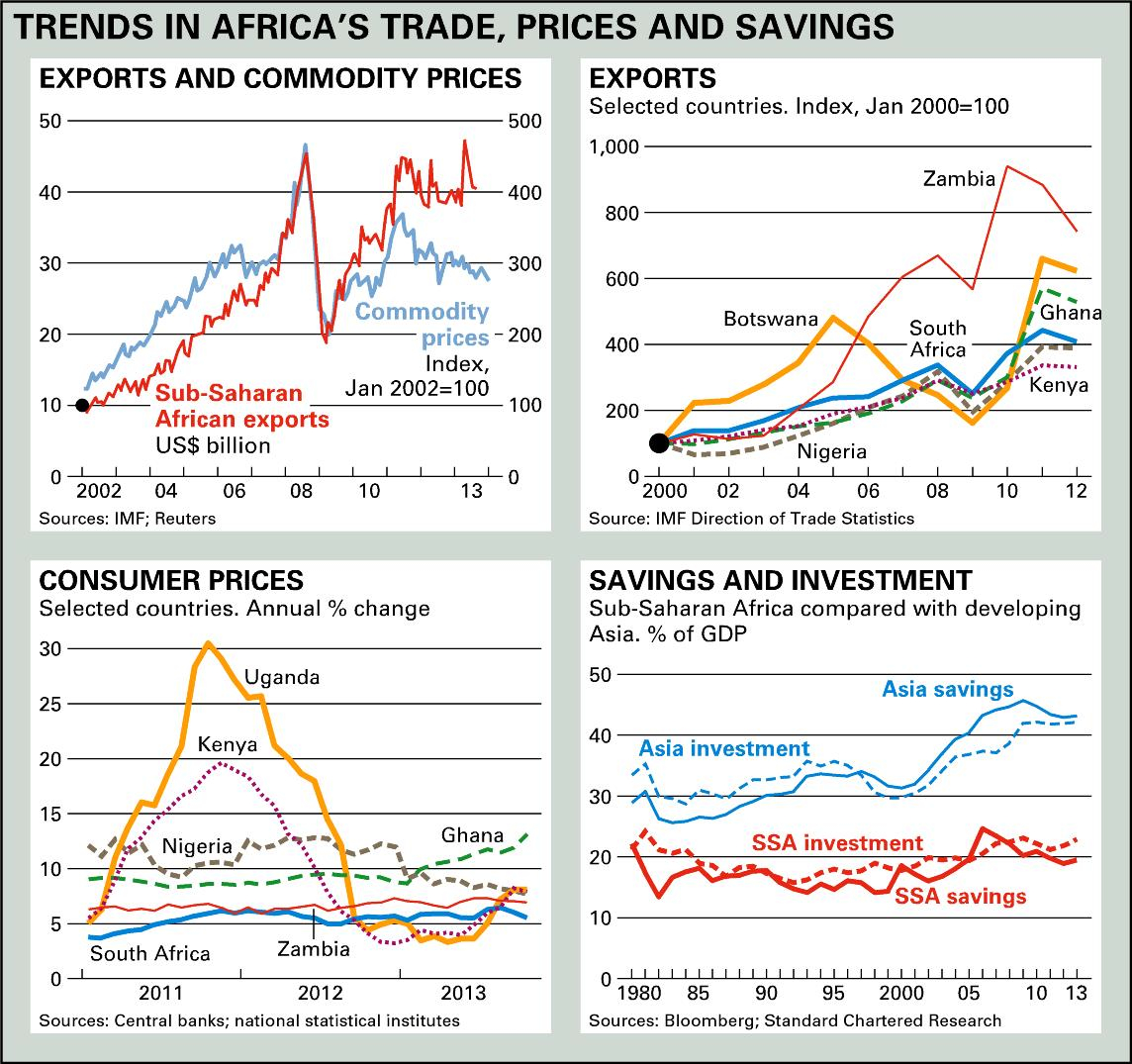

The International Monetary Fund’s projection that Sub-Saharan Africa’s gross domestic product growth should be over 6% in 2014, compared to average Asian growth of over 5%, is an important marker for the continent. Yet Africa’s growth picture is less cheery if North African economies are added: the deepening political crises in Egypt and Libya are holding back regional growth. Tunisia, where the Arab Awakening politics have been somewhat less traumatic than for its neighbours, is still struggling to recover its momentum. However, China, the world’s second biggest economy, is projected to grow by about 7.5% this year which should mean continuing strong demand for African commodity exports.

Few African governments have started the sort of economic transformation that powered the modernisation of Asian economies in the 1980s and 1990s, says development economist Dani Rodrik of Princeton University. He specifies the differences: ‘East Asian countries grew by replicating, in a much shorter time frame, what today’s advanced countries did following the industrial revolution. They turned their farmers into manufacturing workers, diversified their economies, and exported a range of increasingly sophisticated goods’.

So far, Africa’s growth has been driven mainly by better macroeconomic management and export price windfalls for commodities. The next stage is much more problematic. Ghana’s African Centre for Economic Transformation, run by a former head of the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, Kingsley Y. Amoako, concludes that African economies are growing rapidly but transforming slowly.

Ethiopia may prove an exception. Its strategy, which has produced annual growth rates of over 8% for a decade and pushed up agricultural and export production, now uses Asian capital to develop a serious manufacturing base. Just outside Addis Ababa, China’s Huajin Group has opened the first factory in what it says will be a US$2 billion hub for light manufacturing.

Huajin has grand plans to manufacture shoes for the rest of Africa in the factory and boost its workforce 30-fold from its current level of around 1,000. That would be about 5,000 more than its staff in China. Manufacturing wage rates in Ethiopia are about a tenth of those in China. Productivity rates are lower but intense training programmes are pushing them up.

The missing industrial policy

Ethiopia’s policy of ‘developmental authoritarianism’ is familiar to and popular with Chinese companies but few other countries have taken that route. Overall, fewer than 10% of African workers are currently in manufacturing of any kind and only about 1% in modern companies with advanced technology. That’s even lower than in the 1980s. The World Bank reckons that only a quarter of Africa’s young people will find salaried jobs over the next decade. Without substantive economic change, many of the other 75% will struggle to carve out a living from petty trade and small-scale farming. It was that sort of inequality and frustration that drove the uprisings in North Africa three years ago.

None of this is to dismiss the important changes in Africa’s economic circumstances and the signs that the momentum of the past decade is continuing. Indeed, it is these investor inflows, particularly in power, roads and ports, that could lay the foundations for a wider modernisation that would mean Africa starts to process raw materials and gets far more value from its own natural resources. That’s already happening but the scale is far too limited: to change the economic dynamics, there will have to be more effective policies and a determination to face down the vested interests that profit from economic dysfunction and import dependency.

For example, Nigerian billionaire Aliko Dangote is investing $9 bn. in a 450,000 barrel per day oil refinery, petrochemicals and fertiliser plant in the south-west of his country. It’s a move that could start to transform both the national economy and the regional market for refined petroleum products, which is currently supplied mainly by a cabal of Swiss-based oil traders.

More generally, Africa starts the year against a background of relatively positive global growth: the United States and Europe are recovering and Chinese and Asian growth is still strong. That should mean higher demand for African exports, although the investment picture this year will be more complex for Africa if the money managers retreat to more familiar, even if not so profitable, territories.

Two years ago, Africa’s economies were still hit indirectly by the slowdown in Western economies in the aftermath of the 2009 financial crisis. This year, African oil exporters will be vulnerable to a fall in world prices and the longer-term development of shale oil and gas, which will make some of Africa’s biggest markets self-sufficient in energy. Other African economies, according to the IMF, will be vulnerable to the US Federal Reserve, whose ‘quantitative easing’ policy – that is, cheap money to steady the US economy – also encouraged the flow of money to emerging and frontier markets in search of higher yields.

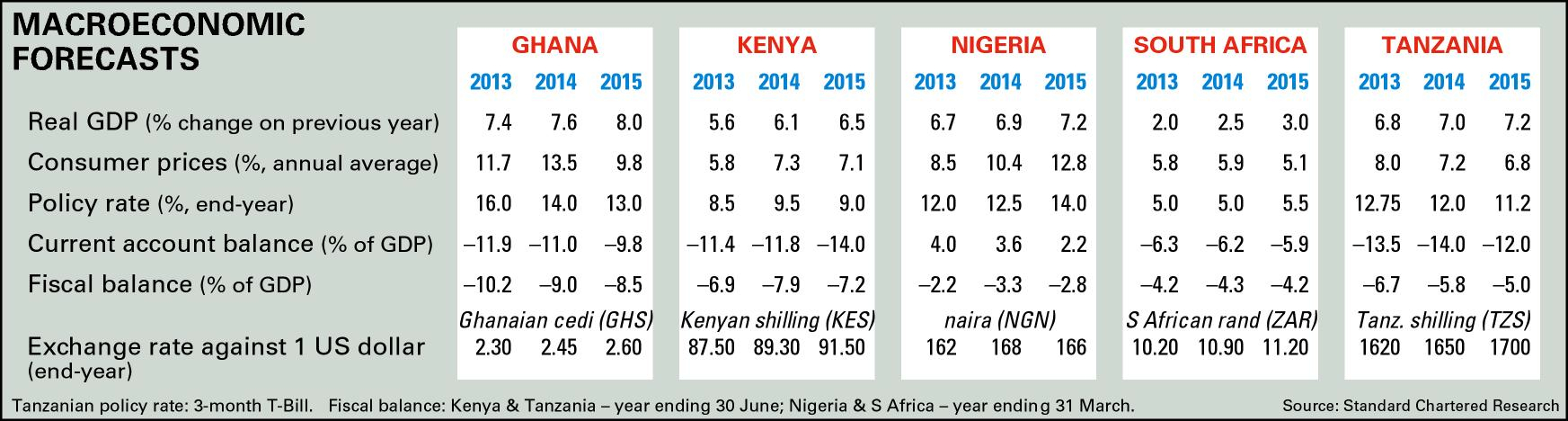

IMF Managing Director Christine Lagarde warned in mid-January of Africa’s vulnerability to the ‘tapering’ of quantitative easing: a rise in US interest rates could reduce investment in Africa. Other institutions, such as Standard Chartered Bank, are more sanguine, arguing that African economies are not particularly at risk, apart from those such as Ghana and South Africa with high fiscal deficits and sharply higher debt levels. Or Nigeria, where political developments around a fiercely contested election in 2015 could coincide with higher US interest rates, prompting nervous investors to reduce equity and debt holdings.

Black star under pressure

Ghana’s economic star has waned over the past year, although the government expects GDP growth to be over 7% this year. Excessive state spending before the close elections in December 2012 pushed the budget deficit back up to 12% of GDP, raising inflation and interest rates but weakening the currency. Since then, the government has struggled to get spending under control.

Ghana’s deficit has prompted criticism from the international ratings agencies in the form of downgrades, as well as public concern from the IMF and independent economic analysts. Reflecting investors’ concerns, the yields on Ghana’s July 2013 Eurobond are higher than the rate on the bonds when issued. As Angus Downie of Ecobank says, high borrowing levels would cause less concern if more of the funds were invested in productive projects or infrastructure (AC Vol 52 No 24, Storm warning) and institutional capacity to plan and monitor spending results was more robust. However the main cause of the budget deficit and the government’s need to borrow is the spiralling cost of its new public-sector pay policy, which sought to standardise pay rates across all sectors of government, from ministries to parastatal companies. Strangely, the government seemed surprised when the trades unions insisted that all pay rates should be levelled upwards.

The closeness of Ghana’s elections in 2012 will make it harder for the government to rein in spending, because of its manifesto promises and its need to prepare for another term in 2016, says Peter Enti, of London-based Africa fund Nubuke Investments. Some believe that President John Mahama will back a crackdown on state spending over the next 18 months. That would enable some relaxation of controls as oil and gas earnings start to rise in the run up to the 2016 polls. In the short term, though, state finances will remain precarious.

Conveniently for Nigerian President Goodluck Jonathan, 2014 is the year the country can claim to be Africa’s biggest economy, even though it will remain a less advanced one than South Africa. Following the completion this year of the recalculation of its national income, known as ‘GDP rebasing’, Nigeria will be officially the continent’s largest economy and the only one in the world’s top 30 by size, ahead of current leader South Africa and of Egypt.

This, says Renaissance Capital’s Chief Economist, Charles Robertson, should further boost investor interest in Nigeria. Former Goldman Sachs Chief Economist Jim O’Neill, who coined the acronym BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India and China) has included Nigeria in a second tier of most promising economies, the MINTs (Mexico, Indonesia, Nigeria and Turkey). This has prompted much debate within the country and beyond. Robertson, who has written extensively about Africa’s prospects for rapid growth, argues that generalisations can be a powerful tool when analysing the international economy. Much of the Nigeria-boosting, local and international, will serve political and financial interests. When a financial chieftain such as Mark Mobius, who manages the $52 bn. US-based Templeton emerging market fund, declares that Nigeria is ‘very, very important’, it’s an assessment that’s hard to ignore.

Kenya, the business base

Much like West Africa’s Nigeria, East Africa’s centre of economic gravity, Kenya, is set to develop as a regional energy, services and manufacturing hub over the next decade. It is the favoured business base for investors in East African oil and gas exploration, production and transport. This year, it will float a billion dollar-plus Eurobond which, according to RenCap’s Robertson, will establish a benchmark rate as other countries in the region also prepare to borrow on the international money markets.

Political worries persist among some investors, who point to Kenya’s involvement in Somalia and South Sudan, as well as the political row over President Uhuru Kenyatta and Deputy President William Ruto’s International Criminal Court trials. Most outsiders remain either oblivious or dismissive of such factors when set against the larger prospect of East Africa, stretching from Ethiopia in the Horn to Mozambique in the south, as the world’s fastest growing energy and commodity exporting region to the Indian Ocean Rim countries.

Those regional prospects boost Kenya’s economic advantages. Its government is in the midst of a boom in infrastructure spending (although it will raise the current account deficit), it maintains a stable currency and a relatively diversified economy. This year, the IMF forecasts Kenya’s GDP growth to stay in line with the average for Sub-Saharan Africa, at just over 6%. Kenya’s neighbours Tanzania and Uganda will also benefit from gas and oil in the medium term.

Yet critics bemoan the snail’s pace of Uganda’s oil development compared, for example, to Ghana’s: commercial oil production is not expected before 2017. Kenya’s size and business environment means that it is unlikely to be challenged as a regional hub. Yet the investment options in the region will expand: Uganda’s GDP growth is set to accelerate to over 6% this year and Tanzania could reach 7%, according to World Bank projections last December.

Maputo's stellar prospects

Gas will also drive development further south, in Mozambique, where major gas finds (supplementing its coal reserves) have attracted international attention. This month, in discussions with Mozambique’s President Armando Guebuza, Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe announced further lending from Tokyo for power plant and infrastructure development projects.

Mozambique’s east coast location should, says Nubuke’s Enti, encourage trade with Asia. There is some concern about this year’s elections but the assumption is that Guebuza will step down and economic policy follow the established path of an uneasy combination of a high growth strategy combined with political patronage (see Feature, Take me to your leader).

In April, the twentieth anniversary of the genocide in Rwanda will focus attention on the country’s stellar economic achievements and the limits of its political authoritarianism. Since 1994, Rwanda’s GDP has grown at an average of 9.6% a year, as evidenced by the boom in non-tradable services, such as construction, transport, hotels and restaurants. Despite some weak fundamentals, such as a modest export base, a large current account deficit and fiscal reliance on donor flows, the country benefits, says Samir Gadio of Standard Bank, from low levels of corruption and efficient economic management under President Paul Kagame’s government, which could effect a structural transformation in the medium term.

However, Rodrik sounds warnings about Rwanda’s authoritarian developmental model: the state sector still dominates investment and much of it is still financed by foreign grants. In the longer term, the question will be whether Rwanda can bring in the local and foreign investment to develop competitive industrial and service companies operating across East Africa. Expect to see a business charm offensive from Kigali to coincide with the annual meeting of the African Development Bank, due in Rwanda in May.

South Africa, which holds general elections this year, will see GDP growth at around 3%, well below the African average. This growth will have little effect on the unemployment rate, which is reckoned at 20-40%, depending on which economist provides the definitions and the core data. The dire state of the political economy is beyond dispute: the year is starting with a host of strikes in the platinum mines and mayhem between rival mining trades unions competing for members.

On the ropes

At the same time, South Africa is far further down the road to structural transformation than any other economy on the continent. Almost half of its exports are manufactured goods and its companies compete effectively elsewhere in Africa against established European, American and Asian rivals. A fast growing Africa could be the locomotive that South Africa needs, 20 years after its first free elections. In the short term, there is growing worry about the weaker rand and the possibility of a ratings downgrade, if political risks increase and there is a serious change to the governing African National Congress at the elections.

South Africa’s relatively high integration into the world economy makes it vulnerable to external shocks: its high current account and budget deficits mean that higher US interest rates could pressurise the Treasury. However, RenCap’s Robertson says that South Africa’s relatively sophisticated markets and global emerging markets will take such wobbles in their stride.

The bigger question for South Africa, as for all Africa’s leading economies, is how determinedly and quickly they can develop more productive and sustainable companies that serve the regional and international markets. For all its financial firepower, South Africa’s development plan still reads more like a wish list rather than a guide to action or even government policy.

Copyright © Africa Confidential 2025

https://www.africa-confidential.com

Prepared for Free Article on 16/07/2025 at 12:24. Authorized users may download, save, and print articles for their own use, but may not further disseminate these articles in their electronic form without express written permission from Africa Confidential / Asempa Limited. Contact subscriptions@africa-confidential.com.